Hacked Mechanics: The Inclusion of Real-Time Mechanics in Interactive Fiction

INTERACTIVE Fiction (also called text-based games) is an important and revered genre in the history of computer games, both as artifacts of study, as well as a venue for creative, artful, and nuanced game development. This is true even in today’s media-saturated landscape, where several recent Interactive Fiction games have gained notoriety and/or popularity.

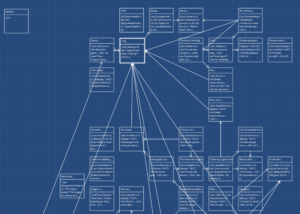

But Interactive Fiction, for the most part, has remained lodged in a state of turn-based mechanics (i.e., they are typically games in which a pre-programmed set of instructions awaits the player’s response) since the genre was conceived. But what if, just like other video game genres, Interactive Fiction continued to function outside of a player’s responses, making moves while the player is considering their next action? What if everything a player did within a text-based game had to happen before or while the game was making its own decisions?

This thesis investigates the possibilities of including a set of real-time mechanics in Interactive Fiction, demonstrates and studies the effects of a select group of real-time mechanics and how they change a player’s experience while playing an Interactive Fiction piece, and ultimately, attempts to forecast how Interactive Fiction may evolve in response to an inclusion of real-time mechanics.

A SHORT HISTORY OF INTERACTIVE FICTION

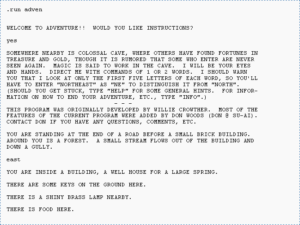

While ELIZA (1964 – 1966) and SHRDLU (1966 – 1970) are reported as the earliest examples of Interactive Fiction, the first game to achieve recognition was Adventure (later named, Colossal Cave Adventure), a game set in an underground cave environment. In Adventure, players were required to type short, one- to two-word commands in which the game would respond in turn. The game ended up spreading across the ARPAnet, inspiring many aspiring computer programmers to develop similar games.

Interactive Fiction then gained popularity in the 1980s with companies such as Adventure International, CE Software, Infocom, and others releasing games like Adventureland, SwordThrust, Zork, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, et cetera. In fact, these games were instrumental in a commercial boom of both computer games and personal computers. In the late 1980s, though, Interactive Fiction (and many of its corresponding subgenres) failed to succeed due to an influx of higher end computers and more graphics-based games.

In the 1990s, Interactive Fiction continued to be developed — often with the inclusion of graphics and sound — but it never regained the popularity that it once achieved. During this time, Infocom re-released several volumes of their early work.

Now, with the advent of the indie game development scene in the 2000s, Interactive Fiction has been gaining traction among fans of the genre, gamers, and game designers alike. In fact, several computer programs have been created in order to aid in the creation of Interactive Fiction. Among them are TADS (The Text Adventure Development System), Twine, Inform, and inklewriter, as well Fungus, a plugin for the popular game engine, Unity 3D. During the 2013 IndieCade Festival, an annual independent games festival in Southern California, the featured seminars made it clear that Interactive Fiction was on the rise.

In 2014, the acclaimed company Inkle (creators of the Interactive Fiction tool, inklewriter) released the game 80 Days, based on the Jules Verne novel, Around the World in Eighty Days. It was since named TIME’s 2014 Game of the Year, among many other accolades.

In the game, players experience lush graphics and sound, while still playing through a classic set of Interactive Fiction mechanics. But unlike some of 80 Days’ predecessors, a few innovative constructs were introduced. For instance, a typical play-through of the game will typically only reveal 2% of the game’s 750,000 words. In fact, there are Easter Eggs and hidden endings in the game that only a reported eight players have ever found. Also, the game experience will vary from player to player depending on the items that are gained and the choices that are made.

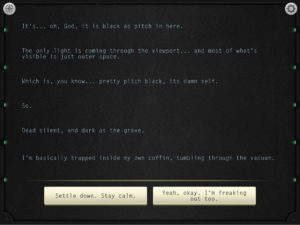

The Lifeline series, by Three Minute Games, is another introduction into contemporary Interactive Fiction. The original Lifeline game, released in 2015, used the mobile platform to its benefit by introducing an interesting notification mechanic in which the in-game counterpart would notify players even when the game was closed in order to get them to come back and play.

Lifeline was determined one of the highest-grossing iOS games in 2015.

Other games have come close to a more real-time approach (e.g., Davey Wreden’s The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide), but these games also rely on a certain amount of non-text-based approaches, like first-person controls, graphics, animation, etc. In this way, these games may be thought of more like other computer game genres and not necessarily true Interactive Fiction.

While Interactive Fiction continues to be developed, it also gains more and more fans. But the core mechanics of the game are still set in a read-and-respond pattern, relating little to other game genres in which playing in real-time is an integral part of the gaming experience.

High-Level Overview

Despite recent innovations in the genre, Interactive Fiction has remained fairly consistent across mechanics, implementation, and gameplay. In order to evolve the form, I am positing that a set of more contemporary mechanics may be implemented.

In looking at two of the more successful recent Interactive Fiction titles, 80 Days and Lifeline, there are several takeaways that may support this issue.

For example, while the core gameplay in 80 Days requires that a player complete a game within eighty days, the time is contained solely within the game itself. For instance, someone might play for five days and then shelf the game for a month, only to come back to Day 5 within the game. What if, the time required for gameplay within the game was also manifested in the real-life time of the player. That is, not playing the game for thirty days in real life would be directly reflected by coming back to an in-game time that is also thirty days later. The result would be a complete fusion of the Magic Circle created by the game with the player’s real life.

Similarly, while Lifeline breaches the Magic Circle by sending player’s notifications outside of the game itself, those notification are merely meant to trigger a response to come back to in-game play. But what if ignoring the notifications resulted in continuing gameplay regardless of whether or not the player actually returned to the game?

These are some of the questions that this thesis aims to answer. Concepts such as real-time gameplay, breaching the Magic Circle with real-life time constraints, and games that live on regardless of player interaction are mechanics that will bring the Interactive Fiction genre back into relevance as well as instigate new design patterns within the genre itself.

FIRST EXPERIMENTS

As a first experiment, I created an Interactive Fiction game called, Three Dragons and submitted it to the 2015 IndieCade festival. While the game did not make it to the final competition, the feedback was favorable and most of the people who played it through the that idea was novel and engaging.

In the game, the player must face a dragon and choose the proper method of either defeating or succumbing to the foe. The twist, in this particular moment, though is that the battle — despite being a text-based sequence — is in real-tie, using a timer to trigger moves by the dragon regardless of what the player is doing. And if the player moves too slowly (or does nothing at all) the dragon will inevitably win the fight.

Three Dragons may be played at the following URL:

http://samoff.com/twine/threeDragons/

Of course, this is just one example that will accompany this thesis.

Basis for Study

There is a wealth of information and study into the history and legacy or Interaction Fiction. But, as far as I can tell, there is no study whatsoever into the idea of real-time mechanics and Interactive Fiction. Following are a list of references that were tapped in order to form the concept of this thesis.

-

Inform. (n.d.). A short history of interactive fiction. Retrieved May 12, 2016, from inform-fiction.org/manual/html/s46.html

-

Interactive fiction – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved January 15, 2015, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interactive_fiction

-

Jackson-Mead, K. (2011). If theory reader. Place of publication not identified: Transcript On Press.

-

Montfort, N. (2003). Twisty little passages: An approach to interactive fiction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

-

Reed, A. (2016). New Frontiers for Interactive Story: A Practice-Based Survey of Emerging Narrative Mechanics (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of California, Santa Cruz, CA.

-

Scott, J. (Director). (2010). GET LAMP [DVD]. USA: Bovine Ignition Systems.

-

Text-based game – Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved September 12, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Text-based_game

-

Wheeler, J. R. (n.d.). IF Theory Reader: Zork, Adventure, and beyond (IF Theory 1) (1st ed.). Place of publication not identified: JRW Digital Media.

While this thesis develops to maturity, this list of references will most likely grow and relevant cites will be interjected into the text.